10x20x40

EN

10 × 20 × 40 takes its name from the standard dimensions of the Colombian brick, the most common and affordable construction unit in the country. Beyond a material, the brick marks a transition—from improvised settlement to casa de material, from rural migration to urban permanence—becoming a symbol of status, stability, and aspiration within the Latin American city.

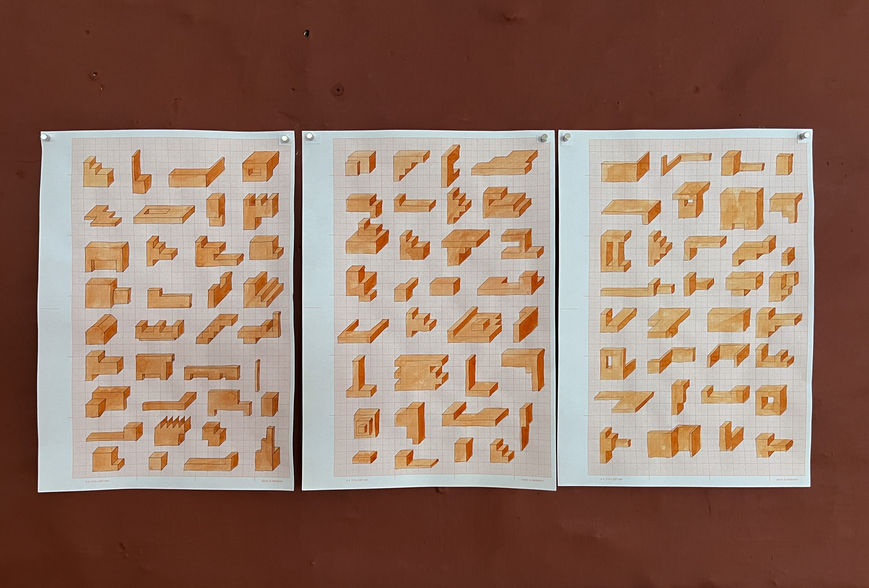

Developed through installation, drawing, and image-based research, the project observes how this single unit has shaped urban landscapes such as Medellín, where decades of migration have produced informal growth, gradual legalization, and dense self-built environments. Alongside the brick itself, the work reflects on contemporary ruins, unfinished structures, housing in the Global South, and questions of land ownership, approaching the 10 × 20 × 40 as both object and system.

ESP

10 × 20 × 40 toma su nombre de las dimensiones estándar del ladrillo colombiano, la unidad de construcción más común y accesible del país. Más que un material, el ladrillo señala una transición: del asentamiento improvisado a la casa de material, de la migración rural a la permanencia urbana, convirtiéndose en un símbolo de estatus, y estabilidad dentro de la ciudad.

Desarrollado a través de diferentes medios de expresión, el proyecto observa cómo esta pieza ha configurado paisajes urbanos como Medellín, donde décadas de migración han dado lugar a procesos de autoconstrucción, ocupación informal y legalización progresiva del suelo. Junto al ladrillo, la obra aborda ruinas contemporáneas, estructuras inacabadas, la vivienda en el Sur Global y las tensiones en torno a la propiedad de la tierra, entendiendo el 10 × 20 × 40 como objeto y como sistema.

Works

Exposición 10x20x40

Abril 2023 Galeria La bruja.

MDE-COL

When did the 10 × 20 × 40 brick stop being a neutral element of the city and begin to register as something meaningful for you?

As an architect, the 10 × 20 × 40 brick has always been present for me. It’s ugly as hell, but incredibly useful. Most of the time it’s meant to be hidden—covered with cement once there’s enough budget for revoque. Yet there are rare examples of buildings that leave the brick exposed and still manage to work architecturally, which is extremely difficult to achieve. There’s no way to escape this brick. It’s our landscape. It’s everywhere. In many ways it makes the city look rough, wild, unfinished—but over time, you learn how to live with it, even how to love it.

The brick often marks the transition from improvised shelter to casa de material. Why is this moment so important in the Colombian context?

In a very crude way, the brick is tied to the story of The Three Little Pigs. The brick house is stronger. The wolf—here, the government—can’t simply come and knock you down once you’ve built with brick. Land invasion is always a gamble, but within that game, the brick is the safest card. It signals permanence. It says: I’m here to stay.

How do migration, land invasion, and legalization shape cities like Medellín, and how is that history embedded in this single construction unit?

Urban growth in Colombia happens both slowly and very fast at the same time. It’s almost impossible to measure or control. It unfolds everywhere at once, especially along the edges of cities. In many cases, this growth reflects the absence of the state. People take advantage of that lack of presence to settle land, which becomes a kind of organic, improvised way of coexisting.

The countryside has been dangerous for decades—people have been displaced, pushed out, left with nowhere to go. That’s why Colombia has a handful of powerful cities instead of a balanced territory. The 10 × 20 × 40 brick represents the final stage of that process, the moment when an improvised shelter becomes a house, when a place starts to feel like a home.

At what point did the project shift from focusing on the brick as an object to understanding it as part of a broader system?

It was never really about the object itself. The brick is a symbol. Materially, it’s fragile, even though it represents stability and permanence. In the exhibition, we built a floor made entirely of these bricks. Visitors had to walk carefully, slowly, which created a strange sense of vulnerability. That contradiction interests me—the tension between what the brick promises and how delicate it actually is. So yes, the focus has always been on meaning rather than the object.

The project combines installation, drawing, and research. How do you approach documentation within the work?

The project can absolutely be read as documentary, and I don’t see that as a problem. I think art creates a space for reflection, and documentation is one way of opening that space. It’s a way of thinking, of listening, of allowing stories and processes to exist without forcing them into conclusions.

Ideas of saturation and emptiness appear throughout the exhibition. How do these conditions relate to contemporary urban life?

Saturation feels very close to our current urban reality, especially in Latin America but also in major cities worldwide. The countryside is emptying out, and at some point it may be inhabited only by machines producing food for megacities.

At the same time, within these dense urban centers there are always gaps—no-places, absences, corners where things didn’t quite fit. Latin American cities are full of these spaces because of accelerated development and lack of planning. I’m interested in them, although this project didn’t explore that dimension deeply. There’s definitely room for another branch to grow from here.

Unfinished structures and contemporary ruins appear throughout the project. What draws you to these spaces?

Honestly, I wouldn’t want to be an urban planner in any Latin American city. It feels impossible. We are so far behind the speed of change that there’s no way to catch up. Politics have failed repeatedly since colonization. Violence, extraction, and greed are deeply embedded in the territory, and this is the architectural result. I can’t imagine these cities becoming something entirely different.

Do you see 10 × 20 × 40 as a closed project, or as an ongoing inquiry?

Human existence has always been a central question for me, and cities are one of its main stages. In that sense, the city is never a closed subject. 10 × 20 × 40 remains open, just like the urban processes it reflects—unfinished, unstable, and constantly transforming.